2024 has reached its mid-point, and planning for 2025 is or should be underway. Consider five initiatives associations should make strategic decisions for as they plan for the upcoming year to ensure their operations remain effective, impactful, and foresight-driven. These five are not in priority order butare seen as a whole.

1- Embrace Digital Transformation and Innovation

Adopt New Technologies

In the fast-evolving digital landscape, adopting new technologies is crucial. Implementing Customer Relationship Management (CRM) systems, leveraging data analytics, and ethically looking at artificial intelligence (AI) can significantly enhance management, optimize operations, and improve decision-making processes.

Virtual Engagement

The pandemic has highlighted the importance of virtual platforms. Developing robust virtual engagement tools for meetings, conferences, and fundraising events can help nonprofits reach a broader audience, breaking geographical barriers and increasing participation.

Cybersecurity

With the increasing reliance on digital platforms, cybersecurity becomes paramount. Strengthening cybersecurity measures will protect sensitive member and organizational data, ensuring trust and compliance with data protection regulations.

2. Prioritize the Long-Term and Environmental Responsibility

Green Practices

Integrating environmentally sustainable practices into daily operations is not just a trend but a responsibility to our communities and global awareness. Reducing waste, minimizing energy consumption, and reducing carbon footprint can set an example for other organizations and enhance the nonprofit’s reputation.

Advocacy and Awareness

Launching campaigns on environmental issues relevant to the nonprofit’s mission can engage local communities and policymakers. Raising awareness and advocating for environmental responsibility can drive significant change and align with broader sustainability goals.

Long-Term Viability

Exploring sustainable funding models is essential for long-term viability. Seeking green grants and partnering with environmentally conscious entities can provide steady financial support while promoting shared values of sustainability. Avoiding short-term decisions that create long-term problems is a must.

3. Foster Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI)

Inclusive Policies

Developing and implementing inclusive policies ensures that diversity, equity, and inclusion are at the organization’s core. This initiative promotes a welcoming environment for all stakeholders, reflecting the values of fairness and respect—emphasis implementation.

Training and Programs

Regular DEI training for staff, volunteers, and board members helps foster an inclusive culture. These programs can address unconscious biases, promote cultural competence, and enhance teamwork and collaboration.

Community Outreach

Ensuring that programs and services are accessible to diverse communities is crucial. By addressing specific needs and barriers, nonprofits can better serve all populations and strengthen their impact on social equity.

4.Strengthen Partnerships and Collaborations

Strategic Alliances

Forming partnerships with other nonprofits, businesses, and government agencies can amplify impact and share resources. Strategic alliances enable organizations to tackle complex issues more effectively and extend their reach. Sponsorships require new thinking. The traditional methods are outdated by 21st-century realities.

Community Engagement

Building solid relationships with local communities through collaborative projects and participatory approaches develops trust and mutual support. Engaging the community in meaningful ways ensures programs are relevant and impactful. Treating chapters and other internal entities, task forces, and committees as partners instead of subordinates is the wave of the future.

Global Networks

Joining international networks and coalitions can open doors to new resources, knowledge, and opportunities for global impact. These connections allow nonprofits to learn from global best practices and adopt innovative solutions to local challenges.

5. Invest in Capacity Building, Leadership Development, Talent Retention and Recruitment.

Staff Development

Investing in professional development opportunities for staff enhances their skills and capabilities. Training, workshops, and educational resources ensure the team remains competent and motivated.

Volunteer Engagement

Creating comprehensive volunteer programs is essential for attracting, training, and retaining committed volunteers. Engaged volunteers are vital assets, bringing passion, expertise, and energy to the organization.

Leadership Programs

Developing leadership training and mentorship programs nurtures future leaders within the organization. Strong leadership ensures sustainability and fosters a culture of continuous improvement and innovation. Invest in Board and Director training. Board and Director training is a sorely needed task that associations have failed to prioritize.

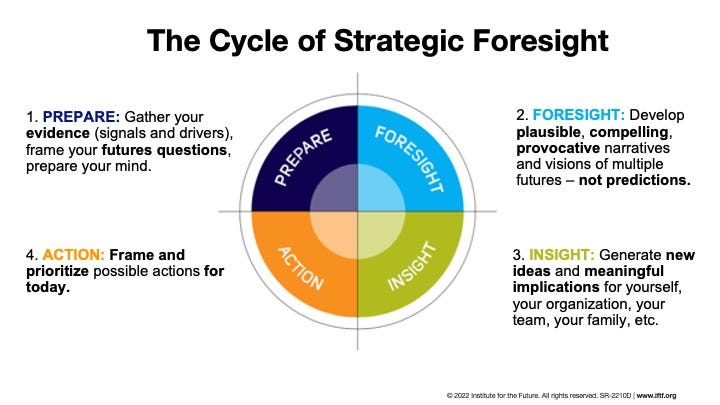

Coda

By focusing on these five initiatives, nonprofit associations can enhance their effectiveness, long-term viability, and ability to fulfill their missions in 2025 and beyond. Traditional strategic planning is not enough. Few strategic plans meet strong foresight thinking. Remember, ensuring that these initiatives are resourced and successfully implemented is the path that will yield sustained growth and impact.